Will Chris Wright Recommit the U.S. to Fighting Global Energy Poverty… Or Just Talk About It?

5 things his remarks tell us about the potential future of U.S. global energy policy

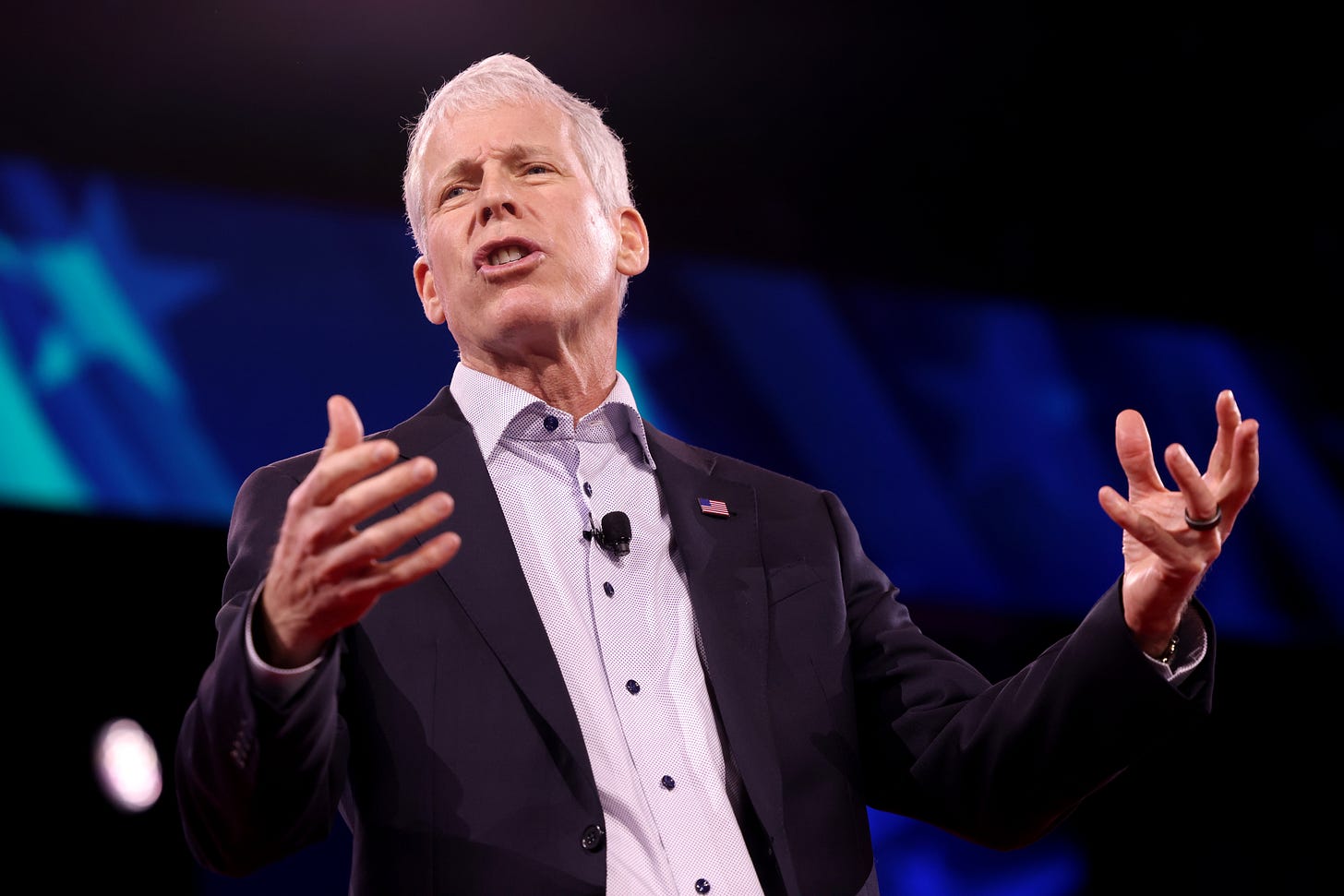

On March 7, U.S. Secretary of Energy Chris Wright took the mic on a small stage at the 10th annual ‘Powering Africa Summit’, a conference dedicated this year to ‘The Future of the US & Africa Energy Partnership’. The mood in the audience—made up of African ministers, investors, entrepreneurs, and policy nerds including myself—was a mix of curiosity, skepticism, and hope.

Just days before, President Trump had called the Southern African nation of Lesotho a country “nobody’s ever heard of”, and dismantled USAID along with its flagship program for energy investment: Power Africa. Was there still any meaningful “US-Africa Energy Partnership” to discuss?

Five things I took away from Wright’s remarks

Secretary Wright genuinely cares about global energy poverty. The Secretary framed affordable, reliable energy as the key to “human possibility, human opportunity, and the quality of life”—the sector of the economy that enables everything else. And he spoke passionately about electricity freeing women from household drudgery, expanding employment, and raising life expectancy around the world. He’s not new to this issue—he’s spoken about it throughout his career. Before the event, people who know him personally had told me that his passion was genuine. And now having heard him, I believe it. Regardless of whether you think his approach is the right one, I think his interest is real.

Wright committed the U.S. to helping solve it with an approach that sounds a whole lot like Power Africa. Given this administration’s assault on foreign aid and the overwhelming uncertainty around its broader foreign policy, I didn’t expect the Secretary to say anything concrete about U.S. assistance. But to my surprise, he made an explicit commitment to U.S. support, while obliquely criticizing traditional “aid-based” approaches. “Government-to-government aid with top-down mandates has just been a disaster,” he said. “We want to be your partners in technology, [and] in providing capital.” For the record, this is exactly what Power Africa did: it deployed public tools to make private energy markets a little less risky and crowd companies, investors, and innovators into the sector. Having worked on Power Africa for years, the erasure of our efforts annoyed me. But if ignoring the virtues of previous programs means the U.S. might remain engaged in global energy access, I’ll take it.

Wright was reassuringly clear-eyed about the bad economics of U.S. LNG as a solution for Africa. Given his history as the CEO of an oil and gas company, some skeptics feared he might disingenuously frame African energy poverty primarily as a chance to export more U.S. liquefied natural gas. But Wright acknowledged that while U.S. LNG has been (and will continue to be) transformative for global markets, it won’t end African energy poverty. Liquefying natural gas and shipping it across the ocean is expensive and simply can’t compete in most African markets. It was refreshing (and reassuring) to hear him acknowledge the economic reality devoid of any overtly commercial or political agenda.

But the Secretary missed a chance to make a forward-looking, “America First” case for clean energy. Yes, Wright led a fracking company. But he’s also worked on solar and enhanced geothermal—and served on the board of Oklo, an advanced nuclear company. Given the breadth of his experience and his bonafides as both an engineer and a conservative, I’d hoped to hear him lay out a vision framing clean energy as a dynamic, rapidly evolving sector full of potential for both African and U.S. investors. He had a chance to push back against the conservative narrative that denigrates the clean technologies he’s been a part of. Instead, he gave them only passing reference. His argument that in reality, we’re far from being able to entirely give up fossil fuels is fair. But his overwhelming emphasis at this event on gas–and especially coal–felt sad and backward-looking. I wanted him to claim this as an era for pragmatism–but also for futurism and innovation. (Too much to ask? Sigh.)

Finally, Wright’s reception highlighted an uncomfortable truth: the Biden administration’s approach to fossil fuels struck a lot of poor people around the world as deeply unjust. In contrast to previous administrations, Wright said, this one will never tell Africans which energy technologies to use or how to develop their own resources: “It’s a paternalistic, post-colonial attitude I just can’t stand.” This earned him warm applause from the African officials in attendance and echoed statements made frequently by African leaders about previous U.S. attempts to limit development finance for fossil fuels. I know that Biden officials took that approach because they genuinely cared about reducing global emissions and wanted to use the tools they had to nudge countries toward cleaner options. I also know that they tried to carve out exceptions for very poor countries–including those in Africa. But if we’re ever going to make progress on global clean energy, we need to admit that too often, that approach was tone-deaf and perceived as deeply hypocritical. And it introduced a strain of distrust and resentment in US-Africa energy discussions that cast a shadow over everything else–and ended up obstructing a lot of progress we could have made together. In the future, U.S. administrations that care about both climate change and global poverty need to do better.

So Wright is an ally… but will it matter?

I think most people left the conference genuinely relieved—but deeply uncertain about what comes next. In an era of extreme distrust and hyperpartisanship around foreign assistance, the Secretary reiterated U.S. commitment to energy poverty, to partnering with African allies, and to using public finance and diplomacy to catalyze private capital. Despite the administration’s reviling of “aid”, this was (mostly) a reassuring continuance of Power Africa’s founding principles and approach.

But now we face a new set of questions. Will Wright have the influence and heft inside the administration to translate his personal commitment into actual policy and resources? Could his Department of Energy (despite historically not having the resources or capacities to implement large-scale programs) take over some of what USAID provided under Power Africa? It’s difficult to imagine at a moment in which they—along with nearly every other agency—are being incoherently slashed. And so far, Wright has remained publicly quiet on cuts to his department. If Wright actually wants to lead on this issue, he’s going to need to fight for resources, attention, and the ability to retain staff expertise.

But his remarks also mean that those of us in this space have a window to push. Not to “save” or “retain” Power Africa exactly as it once existed–but to reinvent it. This means making sure the capabilities that mattered most find new institutional homes; being honest about what wasn’t working–and fixing it; and creating new tools where we need them. (More on that in future posts…).

"Clean" energy is a first world problem, costly, and must be offset and backed up by cheap, energy dense power source wherever employed in any setting. Until every man, woman, and child in the world has access to light and heat, it is damn near malevolent for any ostensibly helpful, public funded organization, private or public, to spend a single penny on such a bourgeoisie fantasy.

Thanks for this measured take on the Powering Africa meeting.

I'm an American professional who has been based in Nairobi for 30 years working on solar and energy access throughout the continent. To me also, the timing of this meeting with the dismantling of Power Africa was unfortunate.

Watching his remarks on YouTube, I agree that Mr. Wright had passion and agree that his comments hit home. You could hear the sizable group of old school African leaders agreeing with the need for larger scale solutions (coal, nuclear gas...), applauding his criticism of Biden era paternalism. In fact, Power Africa never was the transformational program Obama hoped it would be. That's another discussion.

Let's see what Wright and the administration come up with. But let's also be clear. "Paternalistic" climate change arguments are not driving investment in clean energy technologies. Decreasing costs, intelligent interfaces, scalability and decentralized deploy-ability are driving the solar, wind and battery installations that did not feature in his speech. Though US investment plays an important role here, we have lost African markets (and emobility markets) to the Chinese.

Initially, I was inspired by Obama's Power Africa and I was disappointed. I am not inspired by Wright. Let him surprise us.